the business of being offline

the hidden economics of logging off | fhg #77

Before we get into this, a reminder that the Close Friend’s launch offer ends in 7 days. If you’ve been thinking about joining, this is your window.

Happy Sunday financial hotties. Last week, I shared this video on my very draft thoughts on ‘going analog’, and why it’s giving me the ick.

Analog and being offline is being framed as the antidote to burnout, social media fatigue, hustle culture, and generally being digitally overstimulated. And I do get it. We’re living through a time where nearly half of Gen Z and 40% of millennials1 are reporting the highest levels of stress, anxiety and burnout ever recorded. Young adults spend an average of 7+ hours a day on screens outside of work. We are exposed to a very unreasonable number of notifications, news cycles and social comparisons daily. So sure, we’re craving some time offline.

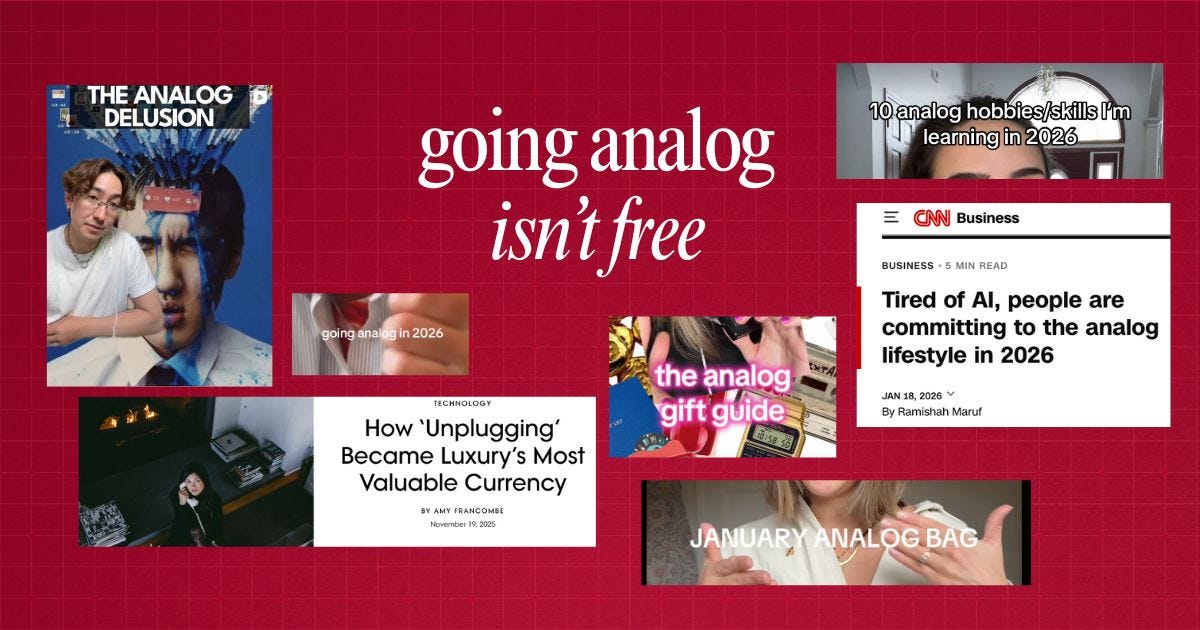

But one thing about a trend is that when it gets rebranded as a luxury, it’s always worth asking one uncomfortable question.

Who can actually afford it? And is this one worth investing your time into? I have an answer, and it’s going to help you make better, more strategic decisions with your time and energy this year.

𝜗ৎ In this issue:

Why staying online is often an economically rational choice

Where exactly are we meant to go if we log off?

Buying the identity instead of building the habit

Offline only works after this exists

The skill is knowing what phase you’re in

Why staying online is an economically rational choice

I watched this video by Eugene Healey recently that finally articulated why the whole “just log off” narrative feels slightly icky to me, which is that being offline is being framed as a brave, enlightened choice, when in reality it only works if you ignore the economic conditions most people are actually living under. Things become status symbols precisely because they’re inaccessible, and going offline is starting to function the same way, because for most people in this economy, building a personal brand is literally a survival strategy. We cannot pretend it’s some kind of whimsical lifestyle choice.

When you’re told your degree might be pointless, your job might be automated, and the thing you were advised to learn five years ago is already obsolete — image, reputation, and visibility often become the only assets you feel you can still control. So choosing to be online can be an economically rational response to the constant instability we face as Gen Alpha/Z/Millenials.

Where exactly are we meant to go if we log off?

What really stuck with me is Eugene’s question of where people are actually supposed to go if they do log off, because we talk about “real life” as if it’s some neutral alternative while Western societies have spent decades defunding and dismantling third spaces, replacing them with monetised, branded versions of community that still require money, time, and flexibility to access.

So when people say “just be offline”, what they’ll often mean is “opt into a version of life that assumes financial buffers you may not have”, which is why I’m sceptical of framing analog living as a universal solution to our generation’s problems — the issue isn’t as binary as being online or offline, it’s pretending those choices are neutral when they both have very real economic costs.

Buying the identity instead of building the habit

What did slightly enrage me was the fact that “analog” trending then immediately turned into an aesthetic you’re supposed to purchase, complete with gift guides, props, tools, notebooks, cameras, flip phones and artisanal accessories for hobbies that I know2 — will end up in a box at the back of a cupboard within a month.

It’s the same pattern we see every January, when deciding you want to be a runner somehow turns into buying the shoes, the watch, the outfit and the water bottle before you’ve built the habit of actually running, and then when running predictably feels uncomfortable, boring, or hard to stick to, the story quickly becomes “this isn’t for me” rather than “I tried to buy an identity instead of change my behaviour”.

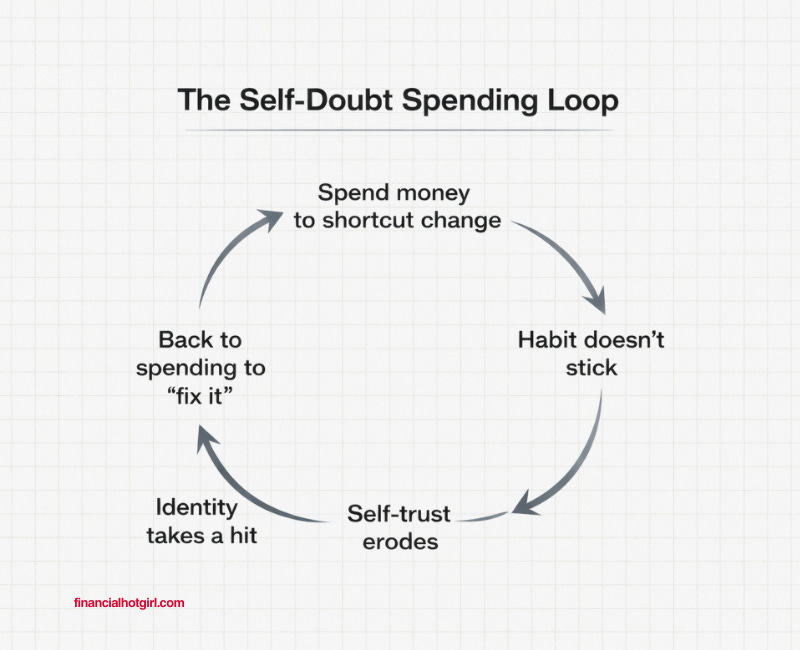

The cost here isn’t just financial (although that adds up quickly) it’s psychological, because every time you spend money trying to shortcut a lifestyle change and it doesn’t stick → your confidence takes a hit → your trust in yourself erodes slightly → you internalise the idea that you’re inconsistent or undisciplined. When in reality, you were sold the illusion that buying the tools, or buying into an aesthetic, would do the work for you.

When consumption of a thing replaces commitment to behaviour change, the most expensive part of that swap isn’t the money you spent, it’s the belief you lose in your ability to change without buying something first.

A Financial Hot Girl micro-philosophy: prove the habit, then own the identity.

Offline only works after this exists

Going offline has a real ROI, I won’t skip past that. It shows up as deeper focus, better thinking, more original ideas and a calmer nervous system, but those returns compound most cleanly once you already have some form of leverage in place. Whether that’s income stability, career capital, an audience, a reputation, or systems that keep working when you’re not actively working on them. Leveraging intense sprints of being online to then be offline.

One of the few takes on this conversation I love is the work CatGPT is doing with physical phones, because it treats going offline as the infrastructure problem that is is.

Her business is built on reducing friction between intention and behaviour without pretending most people can afford to opt out of visibility altogether.

A physical phone acknowledges the digital economy, while creating enough friction to protect attention, limit compulsive use, and still allow people to stay reachable, employed, and connected. In the context of everything in this issue, that’s what a high-ROI version of analog actually looks like — selective participation that acknowledges the real economic trade-offs of modern life.

The skill is knowing what phase you’re in

The most financially literate position here isn’t total withdrawal or constant presence. It’s knowing when visibility is an asset and when “going offline” is actually the best strategic move for your finances, energy or wellbeing. This is why I liked the idea of analog intentionality: not logging off for the performance of it, but deliberately redesigning how technology fits into your life so it stops hijacking your attention without requiring you to opt out of modern life altogether.

When it comes to going analog, the Financially Hot goal is agency. Being able to choose when to be visible, or when to disconnect. Understanding the trade-offs (a key skill, #6 of the 7 that are key for your financial literacy) and building leverage is what a Financial Hot Girl would do in the midst of people rushing to buy their way into a trend.

Being offline isn’t free, being online isn’t evil, and the real skill isn’t choosing one forever, it’s understanding which phase you’re in and making decisions that respect the trade-offs instead of copying a trend and trying to look like you have taste.

—Dev xo

https://www.deloitte.com/global/en/issues/work/genz-millennial-survey.html

https://www.gumtree.com/info/life/p/gumtree/press/brits-waste-money-hobbies/

I’ve got to thank you for the clarity with which you present financial ideas, the diagrams and presenting others work really helps to paint a picture of the problem and give me agency over the solution!

Thank you ! true.